What this article will discuss:

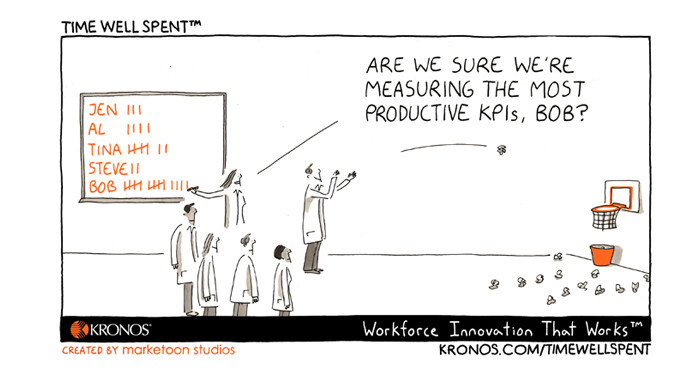

KPIs are a necessary part of performance review, but most are viewed in a vacuum. This article looks at the problems caused by a narrow KPI focus; using an acquisition example.

Why you should read it:

Inappropriate KPIs don't just hinder your ability to measure performance, they can have a direct impact on your bottom line. Focus on the wrong metrics and you could be forcing your employees to work against your best interests.

Setting KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) can be a frustrating box ticking exercise. But it may be more important to the success of your business than you realise. Inappropriate KPIs don't just hinder your ability to measure performance, they can have a direct impact on your bottom line.

The wrong KPIs can encourage short term, narrow thinking. Most KPIs measure one specific performance element, of one department. It's often believed that narrow KPIs which the employee can personally influence heavily represent a fair measure. I just cannot buy that way of thinking.

Granted, you need to judge performance relevant to job roles. But laser-focused KPIs can encourage your employees to act against the best interests of the company. Setting narrow KPIs encourages a narrow focus in your employees. Attaching bonuses to those KPIs imposes that viewpoint with the threat of financial loss.

Let me present an example.

You have to allocate budget between two partners. Up to now you have shared the monthly budget equally between them (£10k each). How would you redistribute your £20k next month based on the below figures?

- Partner A has provided 1000 "New Customers" at a CPA (Cost Per Acquisition) of £10

- Partner B has provided 200 "New Customers" at a CPA of £50

It’s a no-brainer, right? You’d put as much of the spend from Partner B into Partner A as you can until efficiency craters. But what if I told you that customers from Partner A provide an average of £5 in revenue, while customers from Partner B provide £75? If we add this information the equation changes dramatically.

- Partner A has spent £10k and will provide £5k revenue in the next 12 months (ROI = -0.5).

- Partner B has spent £10k and will provide £15k revenue in the next 12 months (ROI = +1.5).

Partner A now has a negative impact of £5k on your bottom line, while Partner B has a positive impact of £5k. Now which campaign are you going to up-weight? Again, it’s a no-brainer right?

Now imagine that in this hypothetical world, your bonus is determined solely by the number of "New Customers" you acquire. If you can deliver 1000 New Customers next month you will get a 10% bonus, and if you deliver less than 1000 you will get nothing. Now which Partner are you choosing? You have to be a really special employee to put the company’s bottom line above your own.

Acquisition Marketers are quick to point out that driving value from customers isn’t their job. I disagree, and have covered that debate in detail HERE. It’s a fundamental fact of business that if you acquire low value customers, the best engagement strategy in the world could not turn them into VIPs.

In this scenario the ‘customers’ you are acquiring exist as numbers on a spreadsheet. I suggest looking at the issue from another angle. Instead of acquiring customers, consider it as acquiring revenue. It's time to replace your meaningless vanity metrics. Bid farewell to "New Customers" and "CPA" and replace them with meaningful KPIs; like "Incremental revenue gained" and ROI.

For most industries it's possible to produce a revenue projection for customers early in their life cycle. If your industry lacks a high volume of transactional data this can be more challenging, but is not impossible. Even with limited data, a basic model can be produced by comparing what you already know about the customer, with the behaviour of similar existing customers. Armed with such a model you can start projecting the incremental revenue you could gain from individual campaigns, partners or channels. Now we can provide early estimates for the impact of marketing activity on the bottom line. Empowering us to make much smarter decision about where to spend our money, much earlier in the process. You don't need to invest in an expensive AI platform to make better marketing decisions, just focus on what truly matters, making money.

Let’s revisit our previous scenario, using the same data, and assuming a model with a 20% margin of error; and an additional 20% human margin for error. *I have included an explanation for these calculations at the end of this article.

- Partner A has spent £10k, and projects to provide £6k revenue (+/- 20%)

- Partner B has spent £10k, and projects to provide £12k revenue (+/- 20%)

Take the most optimistic projection of revenue from Partner A (£7.2k) and the most pessimistic projection of revenue from Partner B (£9.6k). Even with the maximum error, Partner B is still providing considerably more projected incremental revenue to the business. Imagine this projected revenue is now your primary KPI, and determines your bonus. How are you spending your £20k now? I expect your answer is quite different to the one you gave at the start.

Now your goals are truly aligned with the company’s goals, it's almost impossible for you to make the "wrong" decision.

Next year, when it's time to agree on KPIs. Choose metrics that focus your employee's attention, and encourage everyone to pull in the right direction. This approach doesn't just apply to acquisition, it can be rolled out right across the board - just identify how each department impacts the bottom line and create objectives that encourage that activity.

Keep it simple and focus on what really matters.

*Revenue Projection explained*

A margin of error of 20% simply means that the actual value should be within 20% of the predicted value. I have used a conservative 20% for this example, the more sophisticated your model, the lower the margin of error.

In the example above, the actual revenue for Partner A is £5k. A model with 20% margin of error could produce a value between £4k (5000 x 0.8) and £6k (5000 x 1.2). We will assume the maximum margin for error, leading to the most optimistic projection (£6k). Now we must factor in that the decision maker is aware of the margin for error. If the decision maker has a vested interest in this partner and wants them to succeed (eg. perhaps they pushed for the partnership in the first place), they may factor in an additional 20% to account for the error. This would give us an absolute most optimistic projection of £7.2k (optimistic projection + 20% perceived margin of error (6000 x 1.2)).

Now the actual revenue of Partner B is £15k. If we use the same logic to find the worst possible pessimistic projection for Partner B we get £9.6k (15000 x 0.8 = 12000. 12000 x 0.8 = 9600). So even if we take the most optimistic projection for Partner A, and the most pessimistic projection for Partner B, B is still the clear winner.

Additionally, every model will have a confidence level. 95% is a standard confidence level, this means that 19 out 20 times the actual value is within the margin of error. I have deliberately ignored this variable to avoid complicating the equation.

Comments